After two decades of widespread over-prescription of opioid medications and the subsequent rise in problematic use of illicit drugs like heroin and fentanyl, America is embroiled in one of the worst public health crises in our history. Since 1999, trends in drug-involved overdose deaths have steadily been on the rise (Figure 1) — and opioids, both prescription and illicit alike, have been the leading contributors to drug-involved overdose deaths, especially in the past 5 years (Figure 2). In 2021, the opioid epidemic in the United States claimed 207 lives each day, a 37% increase from 2019. [1]

In November 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released updated data suggesting opioid-related deaths have only continued to increase, with an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths occurring from April 2020 to April 2021 (as compared to 78,076 deaths during the same period in the year before).[2] This represents an increase in death rate of 28.5%.[2]

Of those 100,306 drug overdose deaths, the new CDC data shows deaths from opioids made up 75,673, or 75 percent of the total deaths. The prior year’s opioid-related death total was 56,064. Of these deaths over this past year, those related specifically to synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl) and natural and semisynthetic opioids (such as prescription pain medication) have also continued to rise.[2]

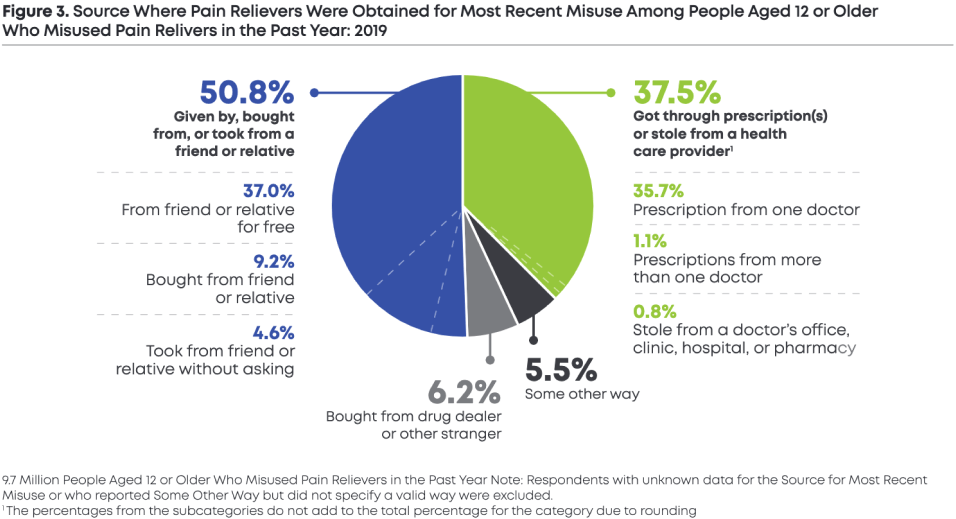

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 73% of individuals who misuse opioids either obtained them via prescription from their doctor (37%) or received opioids from a friend or family member for free (40%). Another 12 percent bought opioids from a friend or family member (9%) and or took from friends/relatives without asking (3%) [2]. Despite long-held beliefs to the contrary, only 6 percent of individuals who report misusing pain relievers purchase those pain relievers from a drug dealer or other stranger. (Figure 3).

While the overall percentage of individuals misusing opioids obtained via prescription from their doctor is 37 percent (Figure 5), the number of opioid-related deaths involving the use of prescription opioids has declined significantly as a percentage of total overall deaths. In 2011, opioid-related deaths involving the use of prescription opioids made up roughly two-thirds (65%) of deaths but declined significantly to 24 percent of total opioid-related deaths in 2020. (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Key barriers to care have largely contributed to the existing gap in OUD treatment access. [3-4] These barriers include the prevailing stigmatization of opioid users, lack of geographic accessibility, and the cost of in-person treatment options as well as other social determinants of health (SDOH).

The public perception is that the opioid crisis is driven, primarily, by illegal fentanyl coming across the border, and that the vast majority of those suffering from OUD are unemployed and homeless. The facts on the ground are quite different. In 2019, the CDC reported that more than two-in-five Americans who reported misusing opioids for pain were employed [40], and one in three developed their opioid dependence initially through a legal prescription from their doctor [5]. A 2020 study in PubMed found that the number of opioid overdoses was nearly 300 percent higher among low-income households than among the homeless (7,170 vs 1,829, respectively). For people struggling with OUD, the stigma associated with OUD persists and discourages them from seeking treatment out of fear and shame.

For people across the United States, the burgeoning cost of care can represent a major barrier to access to treatment. According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, the average cost of a 30-day in-patient treatment program costs $12,500, or $575 per day. In-person facilities also charge for medications and lab tests. [7] Moreover, the cost of in-patient treatment does not account for the financial burden that patients with OUD face if they have to miss work in order to enter treatment. Similarly, with out-patient treatment programs for OUD, when geographic barriers to treatment are not in place, the time it takes to travel to see a provider for in-person appointments on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis, interferes with work and childcare.

The most effective way to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) is with medication. There are three medications — methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone — that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved. [10] The use of these medications has been shown to reduce a person’s risk of continuing to use illicit opioids as well as the risk of a fatal overdose.

In the face of this growing epidemic, the fact that effective treatment exists is good news. However, the fact that these drugs are massively under-utilized only underscores the need to improve access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Many people with OUD also benefit from counseling, but medication has been proven to be beneficial without counseling when counseling services are not accessible or not desired.

Overcoming the barriers to accessing MOUD treatment requires overcoming the stigma, geographic barriers, and high costs highlighted above. A lack of providers able to deliver MOUD, limited funding and reimbursement for MOUD treatment, and the stigma surrounding OUD impede access to these medications.

Geography plays a defining role in determining a patient’s access to care. A 2020 federal report found that 36% of counties throughout the United States demonstrated a high need for buprenorphine services. [6] However, patients in 56% of these high-need counties lack adequate access to providers with the required buprenorphine waivers. [6] At the time of this report, there were 320 high-need counties in the United States with no providers with a buprenorphine waiver. [6]

To date, office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) has made up the majority of treatment options available for patients across the United States. [13] The foundation of this model relies on in-person visits to primary care providers, mental health providers, or specialists who provide in-office evaluations and toxicology testing. Once tests are done, patients are sent to a pharmacy to obtain a buprenorphine prescription, which the patient starts at home. In order for the patient to continue treatment, ongoing in-person appointments are required.

There are additional structured support services available to provide “higher” levels of OUD care that also require time and resource commitments from patients. Examples include:

Because of the access to round-the-clock medical evaluation, certain in-person treatment programs may offer other MOUD medications instead of buprenorphine, including methadone and naltrexone.

Despite the obvious need for widely accessible treatment for people with OUD, traditional options for care have long been underutilized. [15-16] In addition to inadequately addressing existing barriers to care (including geographic accessibility and cost of care), OBOTs and other in-person treatment options are often inflexible in the ways that they require patients to access treatment.

Any treatment program that puts additional strain on a patient’s employment and family responsibilities has the potential to severely increase the likelihood of relapse. [17-18]

For patients with limited local options, a highly-regimented treatment program often doesn’t work. For example, OUD sufferers who travel for work, or care for children or other loved ones, will struggle to access strictly regimented, in-person treatment programs consistently.

Stigma and medical privacy are also concerns in some areas with limited, and highly visible in-person treatment centers. For patients who wish to, or need to, maintain their privacy, it is virtually impossible to receive care with discretion and privacy at an OBOT.

Ultimately, any treatment program that puts additional strain on a patient’s employment and family responsibilities has the potential to severely increase the likelihood of relapse. [17-18]

Overall, traditional in-person OUD treatment options have resulted in significant disparities in care for already vulnerable, high-need patient communities. [19] This is especially true for patients with OUD who may otherwise be a good fit for MOUD through buprenorphine but are located in areas with less access to in-person treatment providers or to providers with buprenorphine waivers. [19]

In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic expedited the emergence of virtual-first healthcare options. With the pandemic impacting patients across the United States, federal and many state regulators acted to waive restrictions on certain virtual treatment options necessary for the effective treatment of opioid use disorder through telemedicine.

In the spring of 2020, the DEA waived the requirement for an in-person visit prior to remote buprenorphine prescribing laid out by the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008. [20] The hope was that by removing these restrictions, patients across the United States would be able to continue to access the care that they needed throughout the course of the pandemic.

Almost immediately, this opened up telehealth care options for patients across the United States struggling with OUD. Whether it be local providers now leveraging telehealth to ensure safe touchpoints with existing patients during the pandemic or overall increased accessibility to outpatient care for those who had previously been unable to access OUD treatment, telehealth use was at a rate 78 times higher in April 2020 compared to February 2020. [21] According to McKinsey, telehealth use had stabilized at 38 times higher than the pre-COVID baseline by 2021 — which suggests the trend in virtual care is here to stay. [21] [39]

Ultimately, the relaxed restrictions on the Ryan Haight Act under the Public Health Emergency have allowed for improved access to more comprehensive OUD treatment via telehealth across the United States. [22] Based on research from peer countries that have similarly relaxed buprenorphine restrictions in the past, this decision has significantly increased access to MOUD treatment for patients. [23]

With a new path toward virtual MOUD available in much of the United States, it’s now possible to scale high-quality telehealth treatment solutions for patients without access to traditional in-person care models. Bicycle Health is pioneering this next phase of OUD treatment with our clinically-proven virtual care platform, which is the first comprehensive model of biopsychosocial, tech-enabled treatment for OUD. [24]

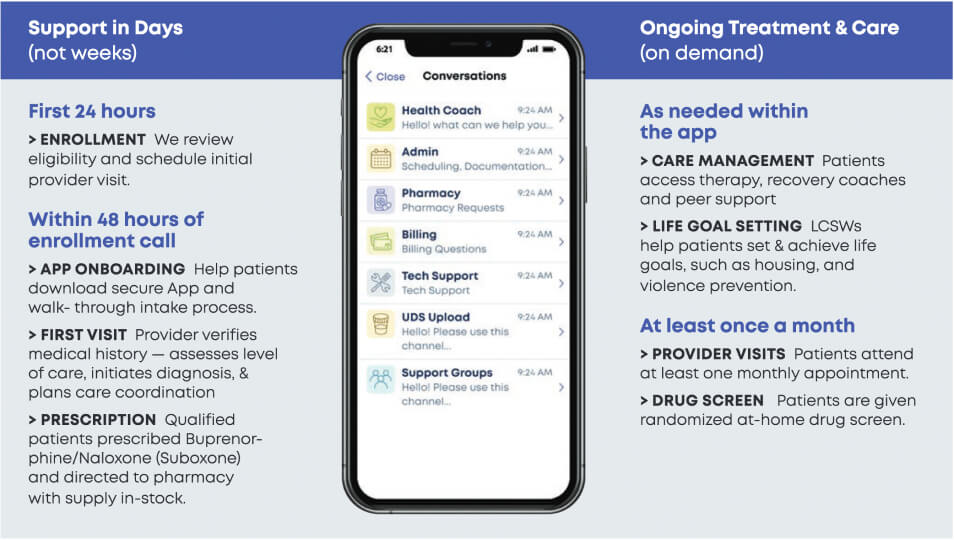

In a descriptive study published in BMJ Innovations, we’ve detailed the telehealth treatment model that Bicycle Health has developed. At the time of this study, Bicycle Health had served more than 10,000 patients across 23 states. Our patient population at the time was 40.2% women and 59.8% men, with an age range of 18–77 years old. Key services and features of our published virtual care model include:

The Bicycle Health virtual care model makes it easier for our clinical team to screen patients for OUD while ensuring they qualify for MOUD via telehealth. Prospective patients can easily schedule an appointment online with our enrollment coordinators who will answer questions, review medical histories, provide details on our insurance and self-pay options, and schedule first appointments. Most Bicycle Health patients are able to see a clinician within 24 hours of their enrollment call, making it easier to access care for those seeking treatment when they need it most.

During the first virtual medical provider visit with Bicycle Health, our providers will help facilitate the downloading of our secure app while getting to know patients. This enables the clinical team to establish immediate touchpoints with new patients while developing a personalized treatment plan for each patient’s opioid addiction.

Bicycle Health’s novel model of care is based on research that demonstrates the need for improved access to buprenorphine treatment as a means to curb opioid morbidity and mortality. [25-27] Our providers are trained and credentialed to prescribe buprenorphine and provide buprenorphine medication management services for all of our patients.

Buprenorphine typically achieves relief of physical withdrawal, cravings, and protection against overdose within 1–2 days of beginning care.

Buprenorphine medication management initially achieves relief of physical withdrawal, relief of cravings, and protection against overdose typically within 1–2 days of beginning care.

The ultimate goal of treatment is sustained cessation of problematic opioid use. To support that, we’ve achieved this goal objectively, Bicycle Health utilizes a drug screening program with randomized at-home testing no less than monthly which may be augmented with directly observed saliva sample collection or in-person testing when necessary.

Bicycle Health’s novel model of care is based on research that demonstrates the need for improved access to buprenorphine treatment as a means to curb opioid morbidity and mortality. [25-27] Our providers are trained and credentialed to prescribe buprenorphine and provide buprenorphine medication management services for all of our patients.

Bicycle Health employs all of its doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and therapists as full-time employees, rather than outsourcing care to contracted providers. Through a HIPAA-secure app, patients are able to speak directly with their medical provider, therapist, or clinical support specialist in one-on-one chats and therapy sessions. Patients can also leverage Bicycle Health’s virtual care platform to attend group support sessions with other individuals receiving OUD treatment.

Bicycle Health recognizes that patients have lives outside of treatment, which is why we also employ a team of licensed clinical social workers who are equipped to connect patients to the resources they need to set themselves up for success outside of treatment. These services include housing, transportation, employment, resources for the prevention of domestic violence, education, and nutrition.

Bicycle Health’s model is organized into regional teams, allowing medical providers, behavioral health sta!, and clinical support specialists to become familiar with the unique resources and populations of their respective regions, thereby optimizing the ability to coordinate across healthcare systems and remotely address individual patients’ SDOH. [29]

Leveraging a telehealth model for OUD treatment is a novel concept, and retention in treatment is the most commonly used measure in published literature for evaluating outcomes. At the time of this study, Bicycle Health’s retention rate at 30 days was 86% for insured patients and 75% for a mixed population of insured and self-pay patients. [33] At 90 days, Bicycle Health’s retention rate was 80% for insured patients and 59% for a mixed population of insured and self-pay patients. [33]

Across the board, Bicycle Health’s retention rates are higher than the industry average for in-person treatment options. While challenging to approximate, given wide inter-program variability, one large claims data review found that the in-person industry average retention rate was only 69% at 30 days and 44% at 90 days. [34]

Another common metric utilized in OUD treatment is the no-show rate for patients. At the time of this study, Bicycle Health’s no-show rate was only 9.5%. [35] The industry average was 23% by comparison (based on a large systematic review). [36]

This peer-reviewed descriptive study published in BMJ Innovations in 2022 has ultimately begun to prove the effiacy of Bicycle Health’s pioneering telehealth model for OUD treatment, which to date has demonstrated stronger retention rates and lower no-show rates when compared to available data for in-person treatment options.

In addition to describing the clinical efficacy of Bicycle Health’s telehealth model, this study published in BMJ Innovations has highlighted the ways the company is improving access to buprenorphine treatment across the United States.

For instance, 70% of Bicycle Health’s new patients are able to establish care with their provider on the same or next business day as their initial enrollment outreach. [37] As part of Bicycle Health’s tech-enabled, collaborative model of integrated medical and behavioral healthcare, 89% of new patients also receive provider-delivered motivational interviewing. [37]

In particular, the implementation of Bicycle Health’s pharmacy finder tool has appreciably reduced the time spent on locating buprenorphine stock and has helped to address financial and logistical barriers for patients in accessing buprenorphine.

Prior to the implementation of the pharmacy finder tool, Bicycle Health’s clinical support specialists spent extensive time locating a pharmacy for each new patient that would be able to fill their prescriptions the same day.

Clinical support staff were only successful on the first call attempt in 40% of cases and would need to call between three to four pharmacies on average to locate stock. [37] Despite this intensive effort, Bicycle Health’s clinical support specialists were still unsuccessful in finding medications in stock on the same day for 10% of patients. [37]

Following the implementation of the pharmacy finder tool, clinical support specialists were able to successfully find stock on the first call attempt in 75% of cases and reduce the average number of pharmacies contacted by 1.5. [37]

With the pharmacy finder tool, the Bicycle Health clinical support sta! are now unsuccessful in finding medication in stock on the same day for less than 1% of patients. [37]

As opioid-related deaths reach new heights in the United States, Bicycle Health’s descriptive research study has revealed far-reaching implications for access to OUD treatment at a time when people need it most. The study finds that the Bicycle Health model is an elective way to reach previously unengaged and unreached populations, demonstrated by 31% of patients reporting no previous history of buprenorphine treatment. [37

In 2021, we saw over 75,000 opioid-related deaths in the U.S. — yet less than 10% of people accessed treatment, usually due to stigma, lack of accessibility, and the cost of treatment. This descriptive review is a major validation of Bicycle Health’s innovative telehealth model as we work to bring e!ective OUD treatment to patients across the country, and ultimately help more people live fulfilling lives free from opioid addiction.

Ankit Gupta – Founder and CEO, Bicycle Health

Medication for opioid use disorder is the gold standard for treatment, and Bicycle Health’s clinically-backed biopsychosocial model for treatingOUD via telehealth can be replicated and adapted to increase widespread access to OUD treatment, opening the door for more people to enter recovery.

Dr. Rebekah L. Rollston – Head of Research at Bicycle Health and lead author of this study

To learn more about Bicycle Health’s clinically proven virtual care model, check out the company’s recent peer-reviewed study in BMJ Innovations.

[1] “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually,” CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, accessed August 31, 2022.

[2] Park, Ji-Yeun Park and Li-Tzy Wu, “Sources of misused prescription opioids and their association with prescription opioid use disorder in the United States: Sex and age differences,” Substance Use & Misuse 55, no.6 (2020): 928-923. DOI: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1713818

[3] “Treatment Settings,” Johns Hopkins Medicine Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Research, accessed July 21, 2021.

[4] Sulley, Saanie and Memory Ndanga, “Inpatient Opioid Use Disorder and Social Determinants of Health: A Nationwide Analysis of the National Inpatient Sample (2012-2014 and 2016-2017),” Cureus 12, no. 11 (2020). DOI: 10.7759/cureus.11311

[5] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives (Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2019).

[6] “Geographic disparities affect access to buprenorphine services for opioid use disorder,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, accessed July 25, 2021.

[7] “Inpatient Rehabilitation,” Drug Abuse Statistics.org, updated in 2022.

[8] Kakko, Johan and Kerstin Dybrandt Svanborg, Mary Jeanne Kreek, Markus Heilig, “1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial,” The Lancet 361, no. 9358 (2003): 662-668. DOI: 10.1016.S0140-6736(03)12600-1

[9] Khatri, Utsha and Corey S. Davis, Noa Krawczyk, Michael Lynch, Justin Berk, Elizabeth A. Samuels, “These Key Telehealth Policy Changes Would Improve Buprenorphine Access While Advancing Health Equity,” Health Affairs Blog, September 11, 2020, accessed July 25, 2021.

[10] “Policies Should Promote Access to Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 24, 2021, accessed July 25, 2021.

[11] Davis, Corey S., and Elizabeth A. Samuels, “Continuing increased access to buprenorphine in the United States via telemedicine afterCOVID-19,” The International journal on drug policy 93 (2021). DOI: 102905.

[12] Wilcox, Clair, “Suboxone vs Methadone: The Differences, Similarities, and Which Could Be Best For You,” Bicycle Health, accessed August 31, 2022

[13] “Public policy statement on the regulation of office-based opioid treatment,” American Society of Addiction Medicine, accessed July 25, 2021.

[14] “Treatment Settings,” Johns Hopkins Medicine Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Research, accessed July 21, 2021.

[15] “National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2020,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSA)’s public online data analysis system (PDAS), accessed December 6, 2021

[16] Duncan, Alexandra, Jared Anderman, Travis Deseran, Ian Reynolds, and Bradley D. Stein., “Monthly patient volumes of buprenorphine-waivered clinicians in the US,” JAMA network open 3, no. 8 (2020): e2014045-e2014045. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14045

[17] Sulley and Ndanga, “Inpatient Opioid Use Disorder and Social Determinants of Health”

[18] Williams, Narissa, Nicholas Bossert, Yang Chen, Urmo Jaanimagi, Marianthi Markatou, Andrew H. Talal, “Influence of social determinants of health and substance use characteristics on persons who use drugs pursuit of care for hepatitis C virus infection,” Journal of substance abuse treatment 102 (2019): 33-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.jstat.2019.04.009

[19] “Geographic disparities affect access to buprenorphine services for opioid use disorder”

[20] “COVID-19 Information Page,” U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA): Diversion Control Division, accessed July 25, 2021.

[21] Bestsennyy, Oleg, Greg Gilbert, Alex Harris, and Jennifer Rost, “Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality?,” McKinsey, July 9, 2021.

[22] Woodru!, Alex E., Mary Tomanovich, Leo Beletsky, Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar, Sarah Wakeman, and Andrey Ostrovsky, “Dismantling buprenorphine policy can provide more comprehensive addiction treatment,” NAM perspectives 2019. DOI: 10.31478/201909a

[23] Fatseas, Melina and Marc Auriacombe, “Why buprenorphine is so successful in treating opiate addiction in France,” Current psychiatry repo!s 9, no. 5 (2007): 358-364. DOI: 10.1007/s11920-007-0046-2

[24] Rollston, Rebekah, Winifred Gallogly, Liza Hoffman, Eshan Tewari, Sarah Powers, and Brian Clear, “Collaborative, patient-centred care model that provides tech-enabled treatment of opioid use disorder via telehealth,” BMJ Innovations 2, no. 8 (2022): 117-122. DOI: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2021-000819

[25] Khatri, et al. “These Key Telehealth Policy Changes Would Improve Buprenorphine Access While Advancing Health Equity.”

[26] “Policies Should Promote Access to Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder,” The Pew Charitable Trusts.

[27] Davis and Samuels, “Continuing increased access to buprenorphine in the United States via telemedicine after COVID-19.”

[28] Kamara, Kaday, “Red Flags and Red Tape Hinder Access to Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder,” University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, July 21, 2022

[29] “COVID-19 Information Page,” U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA): Diversion Control Division.

[30] “Treatment Settings,” Johns Hopkins Medicine Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Research.

[31] Sulley and Ndanga, “Inpatient Opioid Use Disorder and Social Determinants of Health”

[32] “Public policy statement on the regulation of office-based opioid treatment,” American Society of Addiction Medicine.

[33] Rollston, et al., “Collaborative, patient-centred care model that provides tech-enabled treatment of opioid use disorder via telehealth.”

[34] Morgan, Jake R., Bruce R. Schackman, Jared A. Le!, Benjamin P. Linas, and Alexander Y. Walley, “Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population.” Journal of substance abuse treatment 85 (2018): 90-96. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.001

[35] Rollston, et al., “Collaborative, patient-centred care model that provides tech-enabled treatment of opioid use disorder via telehealth.”

[36] Dantas, Leila F., Julia L. Fleck, Fernando L. Cyrino Oliveira, and Silvio Hamacher, “No-shows in appointment scheduling–a systematic literature review,” Health Policy 122, no. 4 (2018): 412-421. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.002[37] Rollston, et al., “Collaborative, patient-centred care model that provides tech-enabled treatment of opioid use disorder via telehealth.”

[38] Sousa, et al., “Perspectives of Patients Receiving Telemedicine Services for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: A Qualitative Analysis of User Experiences,” Journal of Addiction Medicine: July 21, 2022 - Volume - Issue - 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001006

[39] Kaiser Family Foundation - Telehealth Has Played an Outsized Role Meeting Mental Health Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Justin Lo, Matthew Rae, Krutika Amin, Cynthia Cox, Nirmita Pan-chal, and Benjamin F. MillerPublished: Mar 15, 2022

[40] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) - Content source: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/opioids/data.html

[41] Yamamoto, et al, Association between Homelessness and Opioid Overdose and Opioid-related Hospital Admissions/Emergency Department Visits,” Soc Sci Med. 2019 Oct 3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7023863/

Our science-backed approach boasts 95% of patients reporting no withdrawal symptoms at 7 days. We can help you achieve easier days and a happier future.

Get Startedor book an enrollment call